Opioid prescribing in Ontario

Many people in Ontario take opioids prescribed by a doctor or dentist to relieve pain. Opioids have long been shown to be beneficial to relieve sudden, short-duration pain for things like burns, wounds and broken bones, and to ease suffering for people with cancer and those near the end of life.[1] However, the evidence to support their use over the long-term for people suffering from chronic pain, such as back pain, nerve pain and fibromyalgia, is weaker. And, over the last decade, the risks of harm from opioid medications have become very apparent, such as addiction, deadly overdoses, and sleep disorders.[2,3] Prescription opioids, along with illicit use of opioids, have thrust Ontario (and the rest of Canada) into a full-blown public health crisis.[4]

A recent Canadian guideline on opioid prescribing from a team of experts strongly recommends first considering treatments other than opioids for patients experiencing chronic, non-cancer pain. If opioids are prescribed later, the guideline also strongly recommends limiting the daily dose of opioids to reduce the risk of unintentional overdose or death.[5]

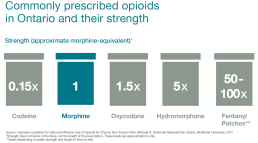

About 44,000 health care professionals prescribed opioids over a one-year period in Ontario, the majority of whom are in family or general practices, and dentistry. Commonly prescribed opioids in Ontario include oxycodone, hydromorphone, codeine, morphine and fentanyl, under brand names such as OxyNEO, Dilaudid and Tylenol 3.

This report looks at the current state of opioid prescribing in Ontario, who receives opioid prescriptions, whether there is regional variation in the province, and the types of opioids that are being prescribed. The report aims to provide an estimate of the number of people who are prescribed opioids as well as the total number of prescriptions filled. These estimates include short-term prescriptions and prescriptions for cancer pain and end of life pain.

The source for the prescribing data reported here is the Narcotics Monitoring System, which collects information on opioid prescriptions (as well as other controlled substances and monitored drugs) filled at pharmacies and other dispensaries across Ontario.

The Narcotics Monitoring System does not capture opioid prescriptions that are filled in hospitals or prisons. The analysis in this report does not include data on street sources of opioids, nor does it include people who filled prescriptions for methadone maintenance treatment or the buprenorphine-naloxone combination drug Suboxone, both of which are used to treat addiction.

The trends in opioid prescribing could be affected by a number of factors, such as changes in government funding, shifts in doctors’ and dentists’ understanding of the evidence, or patient preferences. Even though we cannot fully interpret or explain all of the findings presented in this report, it’s important to keep working toward a better understanding of what we do know about opioid prescribing in Ontario as health care professionals and system leaders work to find solutions to the opioid crisis.

What are opioids?

Prescription opioids, also known as painkillers, include a broad range of medicines related to morphine. They are frequently prescribed to relieve pain. The drugs work by changing the brain’s perception of pain by attaching to receptors in the body’s nerve cells, and generating feelings of elation and relaxation.[6]

Opioids include naturally occurring substances such as morphine and codeine, which are extracted from the seed pod of the opium poppy. Semisynthetic opioids, such as hydromorphone, are derived from morphine, and some opioids, such as fentanyl, are fully synthetic (artificially created).

Buprenorphine/naloxone, and methadone, are both effective opioid replacement therapies for addiction. Note that this report does not include Buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone maintenance treatment in the opioid prescriptions analysis.

Opioids can be beneficial for some people, in some circumstances

For thousands of years, opioids have played an important role in managing pain, from injuries such as broken bones, burns and cuts, or for recovery after surgery.[7,8]

Opioids can also be very helpful for patients managing cancer-related pain and for pain, as well as other symptoms, near the end of life.[9]

Health care professionals’ understanding of how opioids should be prescribed is changing as more research accumulates. Currently, opioids also appear to help carefully selected patients with moderate or severe chronic pain. However, the effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain beyond 12 weeks has not been reliably established through randomized controlled trials, the “gold standard” method for determining whether or not medications work.[10]

Our understanding of opioid-related harms has been increasing

Although widely prescribed to provide relief for people suffering not only acute but also chronic pain, opioids can cause significant harm. Harms associated with opioids include addiction, potentially deadly overdoses, breathing problems during sleep, depression, chronic constipation, osteoporosis, an increased risk of death, and – paradoxically – more pain.[11,12,13,14] Patients taking opioids experience physical dependence, which means they experience withdrawal symptoms if they stop taking the drug or reduce the dose. Abruptly stopping opioids can quickly lead to painful withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, insomnia, hallucinations, excessive sweating, muscle aches, cramping, diarrhea and vomiting, which can last for a week or more. Opioids are addictive and can lead to a compulsive spiral as people taking opioids seek to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Some studies suggest that as many as one out of every eight people taking opioids for chronic pain develop an addiction (sometimes called a use disorder).[15]

Another very dangerous situation occurs when patients resume taking opioids after not having been on them for a while. If they resume taking opioids at the dose they had been used to, they may no longer be able to tolerate this dose, which could result in an overdose. Or if they are unable to get opioids through a prescription, there’s a risk they’ll seek them from street sources for which dose and composition are not reliable, which again could lead to a deadly overdose. In 2015 at least 551 people died in Ontario from opioid overdoses, up from 421 in 2010.[16] Emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning are also increasing in Ontario, up 24% between 2010/11 and 2014/15, from 20.1 per 100,000 people to 24.9 per 100,000 people.[17]

Canada is facing an opioid crisis, as seen by a rising number of overdose deaths, and increasing rates of opioid addiction.[18] The increasing availability of potent new street sources of synthetic opioids is exacerbating the challenge we collectively face. By 2015, fentanyl and hydromorphone became the top two opioids most commonly involved in opioid related deaths in Ontario, both having surpassed oxycodone.[19]

Adverse effects

Dr. David Juurlink, clinical pharmacologist, toxicologist and drug safety researcher in Toronto, on perceptions of opioid harm and benefits versus reality

“Patients who take opioids for chronic pain generally see themselves at low risk of overdose, addiction and death, the drugs’ most serious and unambiguous harms. But there are many other harms that can befall patients who take the drugs as directed. Most of these are dose related. These include constipation (I’ve seen people die of this), falls, fractures, head injuries, motor vehicle collisions, impotence, infertility and osteoporosis.”

“As for the balance of benefits and harms, this can be a very difficult assessment, in part because ‘benefit’ is clouded by the cycle of dependence and withdrawal.”

“In general, the higher the dose, the more likely it is that a patient is being harmed more than helped by therapy. This is a good reason to consider a gradual taper to lower doses.”

Medications to treat opioid addiction

Buprenorphine/naloxone, and methadone, are very effective opioid replacement therapies for opioid addiction,[20] and can reduce the risk of infectious diseases that are transmitted by the unsafe injection of street drugs.[21] Treatment with either drug can also help people like Christine stabilize their lives, restore healthy relationships, and return to work.

“My hip, leg, shoulder and back, all the muscles would contract and they wouldn’t release,” Christine said. “It was like getting a Charley horse, but it could be constant and last for a couple of hours. I was feeling this every day.”

Christine’s story

A registered nurse in Ottawa who suffers from chronic pain after a car collision shares her experiences with opioids – the benefits and the harms

Christine heard the whoosh of the airbag as it inflated in her face. A moment later, the crunch of metal as the hood of her car folded in into the vehicle in front, and then, a dull thud as another car hit her from behind. It was the year 2000, and Christine, a registered nurse, had been on a work call at the time of the collision, travelling at about 90 kilometres an hour along the Queensway highway in Ottawa. She spent a week in hospital, suffering from involuntary muscle contractions down the right side of her body. Doctors didn’t have a specific name for the condition – all Christine knew was that it hurt, a lot.

“My hip, leg, shoulder and back, all the muscles would contract and they wouldn’t release,” Christine said. “It was like getting a Charley horse, but it could be constant and last for a couple of hours. I was feeling this every day.”

Non-opioid therapies

As a nurse, Christine had seen the harms opioids could cause, so she and her doctors decided to try non-opioid therapies to treat her pain. But physiotherapy only seemed to make things worse, and chiropractor treatments, massage therapy and acupuncture didn’t help, either. She did feel some relief from weekly injections of a steroid and a local anesthetic, but the pain persisted.

In 2002, after two years of chronic pain, Christine finally relented and began to take a prescribed opioid, Percocet, a drug that combines the opioid oxycodone with acetaminophen. “I was getting fed up,” Christine said. “At this point, I wasn’t able to go and do my job. I wasn’t functioning anything close to what I was. You’re just scared, and you’re trying to reach for anything. I just wanted some kind of relief.”

When the Percocets were no longer enough because her tolerance had built up, Christine switched to another opioid, hydromorphone. “Once you get a taste of some relief, it takes a little more to get that relief again the next time,” she said. Eventually, Christine’s doctor prescribed her methadone, another opioid that’s often used as a replacement therapy to treat addiction to other opioids, as her main pain medication, along with hydromorphone for breakthrough pain to carry her through the night. This treatment worked well, Christine said, and she stuck with it for five years.

Withdrawal

But trouble began when Christine’s doctor lost his licence (for reasons not related to his prescribing practices), and she and the doctor’s other patients were left scrambling to find other doctors to take on their cases. Christine’s family doctor prescribed her “a very low dose” of opioids for about two weeks. “And that was it,” Christine said, “I was on my own. I don’t blame him, in a way, because they have their own thoughts about [opioid prescribing]. But I was on such a high level. You can’t just stop somebody like that. What it led to was me trying to fix it myself, which didn’t work out very well.”

After five years of taking regular doses of opioids, Christine felt the crush of withdrawal. “When I went through withdrawal from opioids and was left with my pain, it felt like it was 10 times worse,” Christine said. “In the beginning with the withdrawal, it’s just sickness. It’s like having a flu that lasts two weeks. But after that you still have your original pain of why you took the pain meds in the first place.”

Street drugs

Christine looked for any kind of opioid, from other patients she kept in touch with, and bought prescribed opioids from older people who were struggling financially, who sold off their extra opioid supplies to pay for food. Christine moved into community housing in a low-income neighbourhood, and found other street sources of opioids, including fentanyl. “So many different people are using this powdered fentanyl. It’s very scary.”

In the area where she lived, Christine said there were more police cars than cabs. One day, police stopped Christine when she was carrying a stash of illegal drugs. She was convicted on possession charges and sentenced to jail time. While in jail, she lost her housing and ended up in a homeless shelter. “I ended up trying hard drugs when I couldn’t find any opiates,” she said. “I ended up doing crack. It just got worse.”

Housing and help

In 2014, Christine received help from the Housing First program through the Intensive Care Management Program at North East Health. “It helped a lot. The idea is to help the person obtain housing that’s not subsidized – a regular apartment in a regular neighbourhood, not in social housing.”

To treat the addiction to opioids, Christine started a methadone maintenance program. She also began volunteering with a peer support program, and with another research program called PROUD, which performs HIV tests. “Those are things I’m still doing and it’s kind of where I dug myself out,” Christine said.

Telling her story

If she didn’t have previous knowledge about opioids because of her nursing background, Christine said things could have been even worse for her. But one aspect she struggled with was not having any family to support her. As part of her recovery, Christine joined the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s Strengthening Your Voice program, which helps people who have had an opioid addiction tell their story. “I have no shame anymore,” Christine said. “I just want to make sure that people don’t suffer – that’s the only thing that I can hope for. It’s a whole community issue, it’s not just one person did one thing. All of us have to take responsibility for it. Hopefully we can get to a point where people realize that opioids are very dangerous but can be used appropriately.”

Christine says her pain is mostly under control now with methadone, and occasionally some morphine. Through supports from the Canadian Mental Health Association, she also has stable housing. “Life on opioids becomes like a game of Snakes & Ladders, where you’re going down, down, and sometimes you get a little rung up. I don’t know the answer, but we need to keep trying, I know that.”

Based on the most recent data, here’s what we know about opioid prescribing in Ontario:

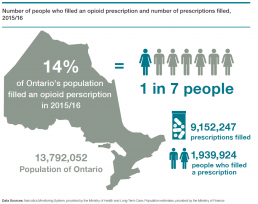

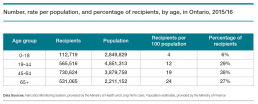

About one in seven people in Ontario filled an opioid prescription.

In the fiscal year 2015/16, nearly 2 million people in Ontario filled opioid prescriptions, about 14% of the population of the province, or one out of every seven people. These include people who filled one-time, short-term prescriptions for opioids, for example, taking codeine after wisdom tooth removal. The numbers also include people prescribed stronger opioids such as hydromorphone.

Despite the unfolding opioid crisis and growing public and professional awareness about the potential harms of opioids, the number of people who filled at least one opioid prescription has not decreased over the last three years. There were 1,939,924 people who received an opioid in 2015/16, compared to 1,927,597 in 2013/14.

During 2015/16, people in Ontario filled a total of more than 9 million opioid prescriptions. In the last three years, the total number of prescriptions filled has increased by about 450,000 to 9,152,247 in 2015/16 from 8,705,218 in 2013/14.

The data do not include opioid prescriptions for addiction treatment (i.e., buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone).

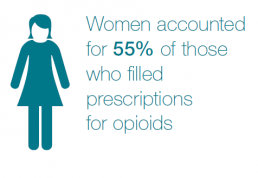

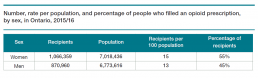

Who is being prescribed opioids in Ontario?

“When someone has been prescribed opioids regularly, they often say that it really surprised them how hard it was to stop taking the opioids.”

A provider’s perspective

Dr. Pamela Leece, a Toronto-based public health researcher and family doctor practicing in addiction medicine, speaks about the challenges of opioid prescribing in Ontario

Weighing the benefits and harms

“There has been a lot of discussion in the media recently around chronic pain prescribing. There are no studies that show the long-term benefit of opioids and the studies that do show some benefit typically lasted three months or less. There’s clinical experience that shows some patients benefit from daily opioids, but for many patients we know that the harm outweighs the benefit for opioid use.”

Difficult to stop

“When someone has been prescribed opioids regularly, they often say that it really surprised them how hard it was to stop taking the opioids. Even people who regularly take a Tylenol 1 over the counter, which contains codeine, might find it very difficult to stop. They’d be having withdrawal symptoms. I don’t think we have a true appreciation for how psychoactive [affecting the mind] and how much physical dependence these drugs have.”

Chronic challenges

“For prescribing, the data that I’ve seen across Canada indicates that Ontario seems to be higher than other provinces. It doesn’t really make sense that two million people in the province would need an opioid each year. If about 20% of the population have chronic pain, very few of them would have an indication for long-term use of opioids. Perhaps more could be done to offer other treatments for pain.”

Reducing the stigma, improving access

“For some people I’ve seen who have unfortunately died of an overdose usually have a very complex situation with addiction, past trauma, mental health symptoms and a stressful social circle and circumstances, and it’s really hard for them to find the complete care that they need. If we reduced the stigma, improved access to care, and integrated health and social services in a really compassionate way for people, we’d be able to improve outcomes for patients.”

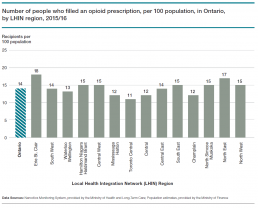

The number of people in Ontario who filled an opioid prescription varies substantially by region.

To look at relative differences in the number of people who filled opioid prescriptions in Ontario’s Local Health Integration Network regions, we examined the number of people who filled prescriptions per 100 people in each region. Variation in the number of people who filled at least one opioid prescription ranges from a low of 11 per 100 people in the Toronto Central LHIN region to a high of 18 per 100 people in the Erie St. Clair LHIN region.

We don’t know the exact reasons for the variation by LHIN region, but it may be partly related to population differences, differences in prescribing practices, or variation in access to non-opioid options for pain control, such as physical therapy. These results are not adjusted for age or sex, which could also account for some of the regional variation.

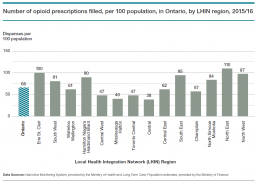

The number of opioid prescriptions filled in Ontario also varies considerably by region.

As with the number of people who filled at least one prescription for an opioid, the total number of opioid prescriptions filled varies substantially by LHIN region, ranging from a low of 38 prescriptions filled per 100 people in the Central LHIN region to a high in the North East LHIN region of nearly triple that number – 110 prescriptions filled per 100 people.

We don’t know the reasons behind the variation in the number of opioid prescriptions filled per population, nor do we know the strength of the dose or length of the prescription.

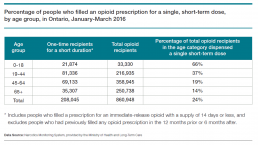

In early 2016, about a quarter of opioid prescriptions filled were for a one-time, immediate-release opioid, and for less than 2 weeks.

There are two main categories of opioid prescriptions – immediate-release and controlled-release – related to how long the effects of the medications last. Immediate-release prescription opioids generally work for three to six hours, while controlled-release opioids only need to be taken once or twice a day to maintain their effects.[22,23] One-time prescriptions for immediate-release opioids can relieve short-term pain for things like wisdom tooth removal, surgery or a broken bone.[24] To get an idea of the proportion of people who fill one-time prescriptions in Ontario, we looked at a three-month subset of the opioid prescriptions filled. Of the people in Ontario who filled an opioid prescription in the first three months of 2016 (January to March), about a quarter (24%) were for short-acting opioids, with a supply of 14 days or less – they hadn’t filled an opioid prescription at all in 2015 and then after the short-term prescription they hadn’t filled another prescription at least up until the end of September (the end of the follow-up period).

About two-thirds of children and youth (aged 0-18 years) who were dispensed an opioid in early 2016 filled a one-time prescription for a short-term, immediate-release opioid, compared to 37% of adults 19-44 years, 19% of adults 45-64 years, and 14% of adults over the age of 65.

Understanding the proportion of people filling prescriptions for a one-time, short duration of pain relief helps us describe a portion of the 2 million people in Ontario who filled prescriptions for opioids. However, the remaining 75% of people who filled a prescription during the same period are not all chronic users of opioids. Some will include those who filled only a few prescriptions for a limited time, or those who filled one prescription for a longer time. What this result tells us is that while there are concerns about the numbers of people in Ontario who are being prescribed opioids, there are some people who are getting a small amount of medications for a short time only – likely to control acute pain.

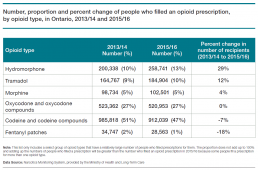

Opioid prescribing by type of opioid has been shifting – hydromorphone and others are up, while codeine, codeine compounds and others are down.

The total number of people who filled opioid prescriptions in Ontario remained mostly steady in the last three years, at about 2 million people. However, the types of opioids in those filled prescriptions has changed in the three-year period from 2013/14 to 2015/16.

The number of people who filled a prescription for hydromorphone increased by more than 58,000 people, or 29%, over three years to 258,741 from 200,338, while the number of people who filled a prescription for codeine and codeine compounds decreased by more than 70,000 people, or 7%, over that same period to 912,039 from 985,818. The number of prescriptions filled for oxycodone and oxycodone compounds, meanwhile, remained almost unchanged over three years at 520,953 people in 2015/16 compared to 523,362 people in 2013/14.

The shift away from codeine toward much more potent opioids such as hydromorphone is very concerning. We do not know why this is happening, especially given increasing awareness of the harms associated with prescription opioids.

Commitment to action

Opioids are at the centre of a public health crisis in Canada and the United States. In November 2016, the federal and provincial health ministers released a joint statement of action to address the opioid crisis, identifying specific actions and committing to fulfilling them. This statement also included commitments from 32 health-related associations and organizations across Canada (including Health Quality Ontario).[25]

We know that about one in seven people in Ontario filled an opioid prescription in 2015/16. We know opioids can be an effective way to relieve pain – in particular, acute pain (e.g., after a broken bone), cancer pain, and pain near the end of life. But we also know that opioids can cause serious harm.

The variation by LHIN region presented in this report appears to demonstrate variable prescribing practices throughout the province (although these could also be results of underlying population characteristics, such as age, average income, and prevalence of chronic conditions). Variation between smaller regions, and between individual physicians, is likely even greater.

Efforts underway

So what efforts are underway to ensure that opioids can be prescribed to ease pain for appropriately selected patients, while also avoiding harm?

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care announced a strategy in 2016 to prevent opioid addiction and overdose.[26] This included a commitment to develop and implement three quality standards – one will guide what quality care looks like for patients living with an opioid use disorder, and the other two will provide guidance on how to prescribe opioids for management of chronic and acute pain. Health Quality Ontario is developing these standards in collaboration with clinicians, researchers, and patients with lived experience. They will be based on the best available evidence for appropriate opioid prescribing, and will be consistent with the Canadian guidelines.

Health Quality Ontario will work with partners to support the adoption of these quality standards through program, service and quality-improvement efforts. These will include developing practical clinical tools and supports, and working with existing programs in Ontario, where appropriate.

The ministry’s strategy also includes training for health care professionals for appropriate prescribing and dispensing of opioids. In addition, Health Quality Ontario will make practice reports available to doctors which enable them to compare their opioid prescribing patterns to that of their peers and to best practices, as well as to strategies for non-opioid, nonpharmacologic pain management options.

The province has also invested in multidisciplinary care teams at 17 chronic pain clinics across Ontario to help patients receive timely and appropriate care to manage chronic pain.[27] Comprehensive approaches to pain management combine the use of medications with physical interventions such as physiotherapy, as well as psychological approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy and self-management education. These comprehensive programs improve pain management and help to avoid or limit opioid use.[28]

For those at risk of an overdose, naloxone kits, which contain an antidote for opioid overdose, were made available without a prescription in pharmacies and community organizations across Ontario, as of June 2016, and by the end of March 2017, the province had distributed more than 28,000 kits to pharmacies, public health units and correctional facilities across the province, available free of charge to anyone in need. [29,30]

Moving forward

The Ontario data reveal that despite some opioids being removed from the list of drugs that are covered by public funding, the use of other types of opioids appears to have increased. Given that there are nearly two million people in Ontario filling prescriptions for opioids every year, this issue needs continued scrutiny and a comprehensive approach for this complex and growing problem to find the best, quickest and most sustainable solutions to reduce opioid-related harms in the population. Opioid prescribing is now receiving a lot of attention, and we will continue to monitor the data to see if the efforts underway are generating results. Millions of people in Ontario are counting on it.

Acknowledgments

Management

Dr. Joshua Tepper

President and Chief Executive Officer

Dr. Irfan Dhalla

Vice President, Evidence Development and Standards

Lee Fairclough

Vice President, Quality Improvement

Mark Fam

Vice President, Corporate Services

Anna Greenberg

Vice President, Health System Performance

Jennie Pickard

Director, Strategic Partnerships

Michelle Rossi

Director, Policy and Strategy

Jennifer Schipper

Chief of Communications and Patient Engagement

Dr. Jeffrey Turnbull

Chief, Clinical Quality

Biographies are posted at:

www.hqontario.ca/about-us/executive-leadership-team

Board

Andreas Laupacis

Chair

Marie E. Fortier

Vice-Chair

Bernard Leduc

Tom Closson

Jeremy Grimshaw

Shelly Jamieson

Stewart Kennedy

Julie Maciura

Angela Morin

James Morrisey

Rick Vanderlee

Tazim Virani

Biographies are posted at:

www.hqontario.ca/about-us/governance

Report development

Health Quality Ontario thanks Christine, David Juurlink and Pamela Leece for sharing their experiences and insights for the stories in this report.

This report was developed by a multi-disciplinary team from Health Quality Ontario, including Susan Brien, Naushaba Degani, Maaike de Vries, Gail Dobell, Ryan Alexander Emond, Louise Grenier, Wissam Haj-Ali, Michal Kapral, Jonathan Lam, Binil Tahlan and Tommy Tam.

Health Quality Ontario thanks the many dedicated people who contributed to this report, including those who reviewed the draft or provided input at different stages of development: Glen Brown, Debika Burman, Jason Busse, Claudette Chase, Tara Gomes, David Juurlink, Mae Katt, Pamela Leece, Diana Martins, Paul Sajan, Mina Tadrous as well as the participants at the Health Quality Ontario/University Health Network Opioid Workshop held in Toronto on February 21, 2017.

Health Quality Ontario also acknowledges and thanks the Health Analytics Branch of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care who provided reviews and data for the report.

Methods Notes

The Methods Notes provide a brief description of the methods used in this report. For more details, please see the report Technical Appendix on Health Quality Ontario’s website.

Data Sources

Narcotics Monitoring System, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

The Narcotics Monitoring System (NMS) is a transaction-based system that collects dispensing data on opioids, controlled substances, and other monitored drugs from pharmacies and other dispensaries across Ontario, irrespective of whether the prescription is paid for under a publicly funded program, through private insurance, or by cash. The information collected in the NMS includes prescriber identification, patient identification, pharmacy and pharmacist identification, date the drug was dispensed, drug identification number and the amount of drug dispensed. The NMS does not include information about monitored drugs dispensed to an in-patient of a public hospital as part of their treatment, but it does include information about dispenses to out-patients of public hospitals and in-patients of private hospitals and health care facilities such as long-term care homes. Also, the NMS does not capture drugs dispensed to people confined to correctional institutions, penitentiaries, prisons or youth custody facilities. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care maintains the NMS, which was implemented in April 2012 and became operational in May 2012. The data used in this report were extracted December 2016.

Population estimates, Ministry of Finance

The Ministry of Finance provides population estimates for the province and for each Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) region. The Ministry of Finance uses the most recent Statistics Canada population estimates by census subdivision as the base for the LHIN region population projections. The method of allocation to LHIN regions varies depending on the geographic makeup of the LHIN region. The estimates used in this report were accessed December 2016.

Corporate Provider Database, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

The Corporate Provider Database (CPDB) is a repository of healthcare provider data. The CPDB contains information on the providers’ reported specialties and postal code of practice. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care maintains the CPDB, with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario providing regular updates on provider credentials. The data used in this report were extracted December 2016.

Analysis

Prescribers

The report describes the number of health care professionals who prescribed opioids. This is a count of the number of health care professionals who prescribed at least one opioid drug in 2015/16, excluding prescribers who only prescribed methadone maintenance treatment or buprenorphine/naloxone.

People who filled an opioid prescription (recipients)

The report describes the number of people in Ontario who were prescribed and filled a prescription for at least one opioid drug in 2013/14, 2014/15 and 2015/16, excluding people who only filled a prescription for methadone maintenance treatment or buprenorphine/naloxone. This measure was calculated as a total count as well as a rate per population for Ontario and the 14 LHIN regions. Rates per population are calculated by dividing the number of people who were prescribed and filled a prescription for an opioid, by the size of the population in Ontario or the LHIN region and are reported using a 100 population denominator. The provincial measure is also described by sex (male/female) and age group (0-18, 19-44, 45-64, 65+) of the person, as well as by type of opioid drug.

Opioid prescriptions filled

The report describes the number of prescriptions filled for opioid drugs in Ontario in 2013/14, 2014/15 and 2015/16, excluding methadone maintenance treatment and buprenorphine/naloxone. This measure was calculated as a total count as well as a rate per population for Ontario and the 14 LHIN regions. Rates per population are calculated by dividing the number of prescriptions filled for opioid drugs by the size of the population in Ontario or the LHIN region and are reported using a 100 population denominator.

One-time, short-term prescriptions

The report describes the proportion of people in Ontario who filled a prescription for a one-time, short-term prescription for an immediate-release opioid drug. The proportion is described in the report by age group (0-18, 19-44, 45-64, 65+) of the person. The proportion is calculated as the numerator divided by the denominator, multiplied by 100:

- Denominator: The number of people prescribed and filled a prescription for an opioid drug in the first three months of 2016 (January to March)

- Exclusions:

- Methadone maintenance treatment or buprenorphine/naloxone

- Exclusions:

- Numerator: The subset of the denominator that included any person who had a single prescription filled for an immediate-release opioid drug with a supply of 14 days or less in the first three months of 2016 (January to March)

- Exclusions:

- Anyone who had an opioid prescription in the 12 months prior to the single short-term prescription filled (January to December, 2015)

- Anyone who received a subsequent prescription in the 6 months after the single short-term prescription filled (April to September, 2016)

- Exclusions:

List of opioids

A list of types of opioid drugs included in the analysis of this report (there were also opioids included in the report that did not fall into one of these types):

- Buprenorphine

- Codeine and codeine compounds

- Fentanyl patches and tabs

- Hydromorphone

- Meperidine

- Methadone for pain

- Morphine

- Oxycodone and oxycodone compounds

- Oxycodone/Naloxone

- Tapentadol

- Tramadol

References

[1] Teater D. Evidence for the Efficacy of Pain Medications. National Safety Council. Available from: http://www.nsc.org/RxDrugOverdoseDocuments/Evidence-Efficacy-Pain-Medications.pdf

[2] MOHLTC Strategy to Prevent Opioid Addiction and Overdose, October 2016 https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2016/10/strategy-to-prevent-opioid-addiction-and-overdose.html

[3] Von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R. Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2011. 155(5):325–328. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3280085/

[4] Public Health Agency of Canada. Statement from the Chief Public Health Officer: Pharmacists Help Address the Opioid Public Health Crisis in Canada. March 13, 2017. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2017/03/statement_from_thechiefpublichealthofficer pharmacistshelpaddress.html

[5] Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ, 2017. 189:E659-E666. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/189/18/E659.full

[6] Health Canada. Opioid Pain Medications, 2009 http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/alt_formats/pdf/iyh-vsv/med/ana-opioid-med-eng.pdf

[7] Booth M. Opium: A history. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1986.

[8] Zimmerman DL, Stewart J, Postoperative pain management and Acute Pain Service activity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. June 1993, Volume 40, Issue 6, pp 568–575.

[9] Teater D. Evidence for the Efficacy of Pain Medications. National Safety Council. Available from: http://www.nsc.org/RxDrugOverdoseDocuments/Evidence-Efficacy-Pain-Medications.pdf

[10] Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 218. AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available from: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/557/1971/chronic-pain-opioid-treatment-report-141007.pdf

[11] Von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R. Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2011. 155(5):325–328. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3280085/

[12] Brush DE. Complications of Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Management of Chronic Pain: the Paradox of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia. Journal of Medical Toxicology. (2012) 8:387–392. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3550256/pdf/13181_2012_ Article_260.pdfStatistical Journal of the IAOS, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 67-87, 2015. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716822/

[13] Yi P, Pryzbylkowsk, P. Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia. Pain Medicine 2015; 16: S32–S36. Available from: https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/painmedicine/16/suppl_1/10.1111_pme.12914/2/16-suppl_1-S32.pdf

[14] Vuong C, Van Uum SH, O’Dell LE, Lutfy K, Friedman TC. The effects of opioids and opioid analogs on animal and human endocrine systems. Endocrinology Review, Feb. 2010.31(1):98-132.

[15] Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015 Apr;156(4):569-76.16

[16] Office of the Chief Coroner, Ontario Forensic Pathology Service. Ontario Opioid Related Toxicity (2010-2015). Note: The 2015 figure is preliminary figure, and subject to change.

[17] Canadian Institute for Health Information, Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Hospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits Due to Opioid Poisoning in Canada – Data Tables. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2016.

[18] Government of Canada. Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis. November 19, 2016. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-abuse/opioid-conference/joint-statement-action-address-opioid-crisis.html

[19] Gomes T, Greaves S, Martins D, et al. Latest Trends in Opioid-Related Deaths in Ontario: 1991 to 2015. Toronto: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; April 2017. Available from: http://odprn. ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ODPRN-Report_ Latest-trends-in-opioid-related-deaths.pdf

[20] Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002207. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4.

[21] Williams AB, McNelly EA, Williams AE, D’Aquila RT. Methadone maintenance treatment and HIV type 1 seroconversion among injecting drug users, AIDS Care , 1992, vol. 4 (pg. 35-41).

[22] Health Canada. Opioid pain medications frequently asked questions. November 2009. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/iyh-vsv/med/opioid-faq-opioides-eng.php

[23] Michael G. DeGroote National Pain Centre, McMaster University. Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. Glossary. Available from: http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/cgop_b_glossary.html

[24] Kaplovich E, Gomes T, Camacho X, Dhalla I, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN. Sex Differences in Dose Escalation and Overdose Death during Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015; 10(8): e0134550. Published online 2015 Aug 20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134550

[25] Government of Canada. Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis. November 19, 2016. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-abuse/opioid-conference/joint-statement-action-address-opioid-crisis.html

[26] MOHLTC, Strategy to Prevent Opioid Addiction and Overdose, October 2016. Available at https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2016/10/strategy-to-prevent-opioid-addiction-and-overdose.html

[27] MOHLTC, Strategy to Prevent Opioid Addiction and Overdose, October 2016. Available at https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2016/10/strategy-to-prevent-opioid-addiction-and-overdose.html

[28] Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, Fu R, Dana T, Kraegel P, Griffin J, Grusing S, Brodt ED Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.7326/M16-2459.[Epub ahead of print]

[29] Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Naloxone Program for Pharmacies. June 24, 2016. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/naloxone.aspx

[30] Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Naloxone Now Available in Over 200 Cities and Towns in Ontario. April 11, 2017. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2017/04/naloxone-now-available-in-over-200-cities-in-ontario.html?utm_ source=ondemand&utm_medium=email&utm_ campaign=p